Amanda Boulos

The Legend of the Palestinian Sasquatch

10.31–12.07.2024

Room 2

10.31–12.07.2024

Room 2

"This is one more reason why fiction and research are equally necessary: they are all that remains to fill the silences handed on with the vignettes from one generation to the next."

— Alice Zeniter, The Art of Losing

Sasquatch comes from the Sts’ailes’ Halkomelem word sásq’et, meaning hairy man. Colloquially, it is the word Canadians use to refer to what Americans call Bigfoot—a mythical creature that lives in mountain landscapes in North America. The terms that come up when a Sasquatch is being described are: big, tall, giant, enormous, strange, unidentified, human-like, ape-like, and always hairy. Although their existence is contentious, Sasquatch has been the interest of settlers and Indigenous peoples across various countries and landscapes.

Mythology can be approached in two ways. One with scepticism, centering one’s own beliefs and world. The other with kindness and a sense of openness. While fascination can exist in both approaches, the intent—sometimes subconscious and personal, at other times institutional and violent—makes all the difference. Amanda Boulos opens a parallel between the mythology of the Sasquatch, the pursuit to catch it, and the way host countries can mythologise the lives of migrants, including Palestinians.

Before he moved to Canada, Boulos’ maternal grandfather was one of the best bare-knuckle boxers in Beirut (Lebanon). He would take part in competitions and was quite a public figure—known for his stoic and fearless nature. With his move to Canada, his merits and accreditation weren’t met with the same regard, as with many migrants and refugees. In a way, his life pre-migration—and a part of himself—became legend. It is perpetuated in stories that run in the family and in other countries.

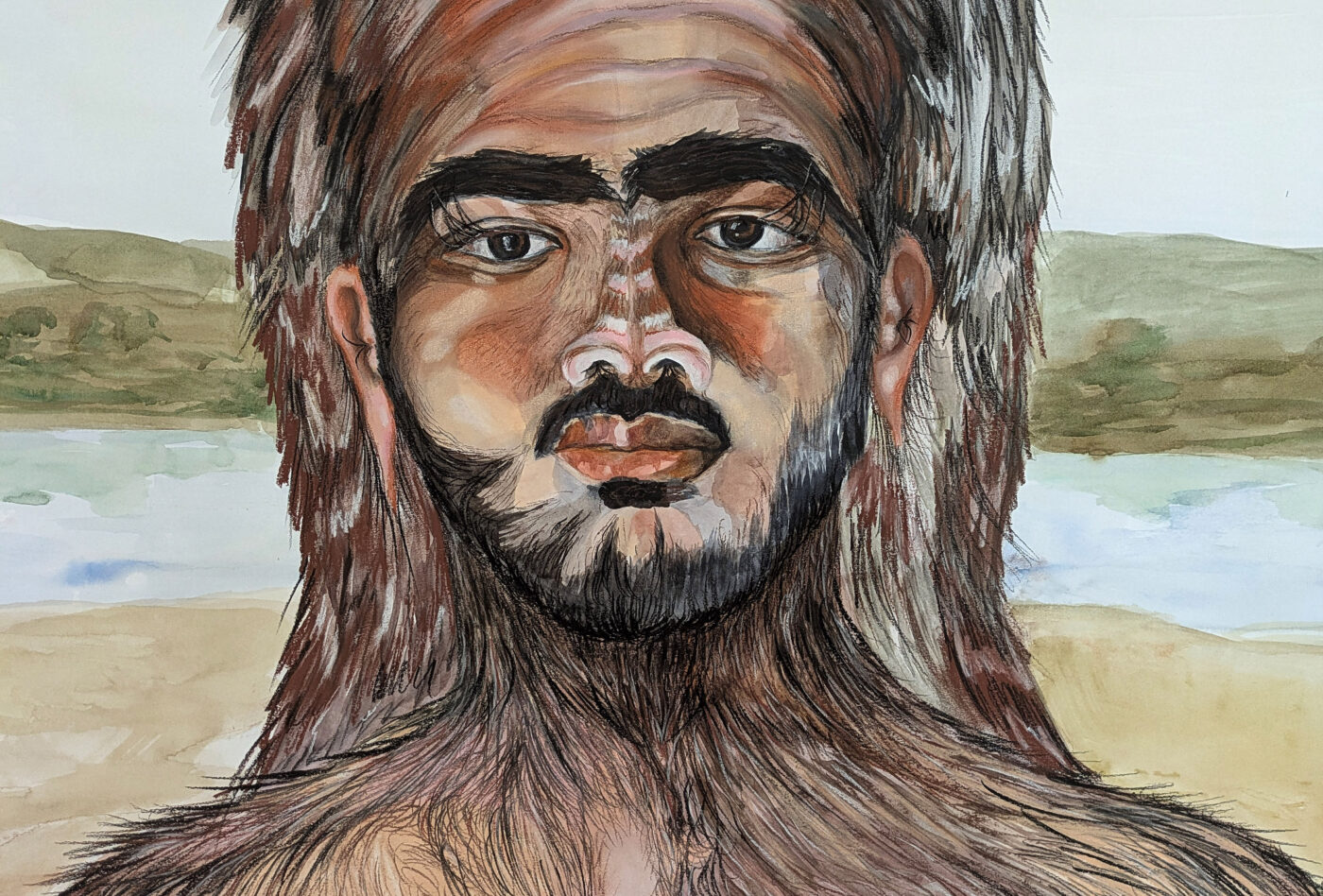

The Legend of the Palestinian Sasquatch is where Boulos explores her family’s oral narratives from Palestine, Lebanon and Canada, as well as her own life. The show includes four large drawings of Sasquatches, which her male family members modeled for her. They are accompanied by a series of landscape paintings from different places she has visited and lived in: Prince Edward Island, Alberta—where she first started thinking about this body of work in 2019—Lebanon and Palestine. Boulos complements these landscapes with depictions of long-distance migratory species; the Painted Lady butterfly and the Arctic Tern bird. She traces places that she and her family moved to and from, in an attempt to discover who they were before the move, before the state’s mythologisation.

The landscapes are portrayed from an aerial view, as if captured by drones. Boulos’ interest in lands and their representation extends to questioning what abstraction does to bodies, especially in relation to airstrikes in Palestine and Lebanon. Scanning a landscape from above requires a violent and mechanical distance between body and shooter.

Settlers looked at Sasquatches as something, not someone. Records note how many people have seen one before, where exactly, what it was like. A Sasquatch is always caught in a glimpse, passing by, roaming around a landscape—an eye scans a landscape to find it. Many remain sceptical, insisting on the monstrosity of the human-like creature. In Canada, this act of othering extends beyond the mythology of the Sasquatch, and into the experiences of marginalised and migrant bodies.

The Sasquatch in Indigenous cultures is perceived differently, as a spiritual being that moves between human and nature. Kelsey Charlie, a Sts’ailes’ band councillor, notes that seeing a Sasquatch is “considered a blessing and a sign of good luck.” His grandfather would tell him that good fortune is going to come your way.

In Centre CLARK’s gallery, the Sasquatches are not caught in a glimpse. They stand tall, facing us, with their long lashes and thick eyebrows. Pride and certainty accompany fascination. The hairs overflow, ornamenting bodies that had once been orientalised, shamed and othered. The hair follicles’ rhythm is steadfast. If their labour is shaved off, it will persist—unwilling to do otherwise.

— Sarah Sarofim